Richard Kuhn (1900–1967)

Professor of general chemistry at ETH Zurich

Richard Kuhn was born in Vienna on 3 December 1900. He was one of two children to Richard Kuhn, an imperial-royal privy councillor and engineer, and Angelika, a primary school teacher née Rodler.

Initially taught by his mother, Kuhn attended the same school as future physicist and Nobel laureate Wolfgang Pauli from 1910 to 1918.

Studies

After having passed the school leaving examination he did his national service.

In the winter semester of 1918/19, he embarked on a degree in chemistry at the University of Vienna, which he continued under former ETH Zurich professor and Nobel laureate Richard Willstätter at the University of Munich from the following winter.

He completed his doctorate in 1922 with the thesis "Über die spezifischen Eigenschaften der Fermente". He qualified as a professor in 1925 with a paper entitled "Beitrag zum Konfigurationsproblem der Stärke".

ETH Zurich and Marriage with Daisy Hartmann

In 1926 he was selected from 32 candidates to succeed Hermann Staudinger, who was moving to the University of Freiburg im Breisgau, at the ETH Zurich's Chair of General Chemistry. Here, Kuhn began to conduct research into vegetable carotenoids and vitamins. At the University, he met pharmacy student Daisy Hartmann, whom he married in 1928. The marriage produced six children. In May 1928, however, Kuhn requested that his tenure not be extended when it ran out on 30 September 1929.

Time in Heidelberg

From October 1929 he was Head of the Department of Chemistry at the newly founded Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Medical Research in Heidelberg and an honorary professor of chemistry at the university. In 1936 he became temporary, in 1937 Managing Director of the Institute of Chemistry at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute. 1938 was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his research on carotenoids and vitamins. Citing the Nazi government's decree from 1937 prohibiting scientists in Germany from accepting the Nobel Prize, however, he turned down the award.

Second World War and invention of poison gas

As an Austrian, Kuhn did not have to join the NSDAP but – according to the current state of research – compensated for this with his all-German convictions and adaptation to the regime. In 1933 he dismissed his Jewish members of staff. In order to secure resources for his own research and further his career, he also denounced a colleague who continued to employ Jewish workers. When the war began, Kuhn investigated means of protection against chemical warfare. Conversely, from 1940 he conducted research into vitamin inhibitors on behalf of the Wehrmacht with regard to their use as chemical weapons. At the end of 1942, Kuhn additionally turned his attention to poison gas research. Initially, he sought defence substances to protect one's own troops. After the supposed antidote actually augmented the effect of the novel nerve gases Tabun and Sarin even further, however, he developed the poison gas Soman, which was – and still is to this day – far more lethal than the other two due to the lack of medical treatment possibilities. As a member of the war research network, he was also indirectly involved in experiments on humans.

Cooperation with the Allies

In autumn 1944, files on Soman research were removed from Heidelberg by chemical officers, documents and letters on other projects destroyed. For lack of concrete documentation, Kuhn was able to convince the Western Allies that he had actually prevented worse in his various functions within war research. His willingness to cooperate with the Western powers and their interest in his biochemical knowhow enabled him to continue on as Head of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Medical Research (which would eventually be renamed the Max Planck Institute for Medical Research). From 1948 he was Secretary of the Supervisory Board, from 1954 Chairman of the Chemistry, Physics and Technology Section and from 1955 Vice-President of the Kaiser Wilhelm/Max Planck Society.

Nobel Prize

In 1949, Kuhn was re-awarded the Nobel Prize he had rejected in 1939 and travelled to the USA several times during the 1950s, amongst other things to advise colleagues there from the earlier chemical weapon projects. In a commemorative publication on the history of the Kaiser Wilhelm/Max Planck Institute in 1961, he declared science ethically neutral and under an obligation to act purposefully, which includes both the medical preservation of life and its military destruction.

Kuhn died in Heidelberg on 31 July 1967.

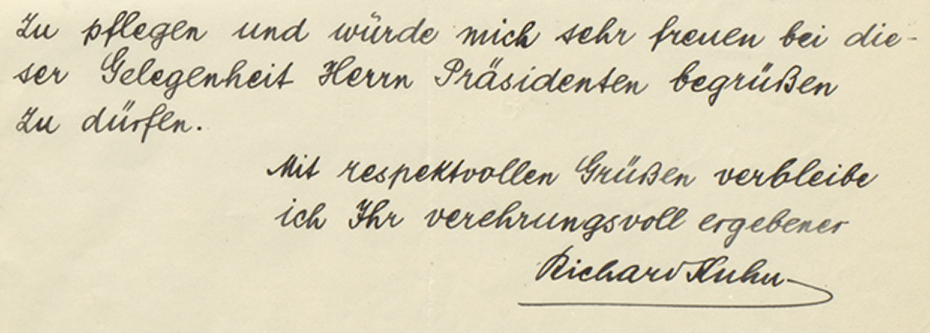

Manuscript

Holdings

ETH Zurich's University Archives at the ETH Library contain the Historical School Board Archive with documentation on Richard Kuhn's chair. A correspondence spanning thirty-four letters between Richard Kuhn and Arthur Stoll (1887 to 1971), a professor of chemistry at the University of Munich and Director of Sandoz AG Basel, from the years 1932 to 1957 is archived in the combined personal papers of Richard Willstätter and Arthur Stoll.

Literature

- Maier, Helmut, & Gesellschaft Deutscher Chemiker. (2015). Chemiker im Dritten Reich: Die Deutsche Chemische Gesellschaft und der Verein Deutscher Chemiker im NS-Herrschaftsapparat. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH.

- Deichmann, Ute. (2006). Richard Kuhn, 1900-1967: Stellungnahme der Gesellschaft Deutscher Chemiker zu seinem politischen Verhalten während der NS-Zeit unter der Fragestellung: Kann Kuhn als Persönlichkeit Vorbildcharakter in der Chemie zuerkannt werden. Online-Publikation.

All Nobel Prize laureates of ETH Zurich at a glance